Original Item. One-of-a-Kind. This is the most tremendous military musical instrument we have ever offered. This is a banjo attributed to Private Needham Roberts, who was on sentry duty with Henry Johnson on May 14th, 1918, when they were both attacked by a German raiding party consisting of at least 12 soldiers. While under intense enemy fire and despite receiving significant wounds, Private Johnson mounted a brave retaliation, resulting in several enemy casualties. When his fellow soldier (Needham Roberts) was badly wounded, Private Johnson prevented him from being taken prisoner by German forces. Private Johnson exposed himself to grave danger by advancing from his position to engage an enemy soldier in hand-to-hand combat. Wielding only a knife and gravely wounded himself, Private Johnson continued fighting and took his Bolo knife and stabbed it through an enemy soldier's head. Displaying great courage, Private Johnson held back the enemy force until they retreated.

The back of the banjo head is inscribed:

Needham Roberts

Used in front lines

Séchault, France

Sept. - Oct. 1918

369th U.S. Inf.

The inscription is certainly done period, and is accurate to the positions of the 369th at the time. The 369th took the French town of Séchault on September 29th and held it until war’s end, with a memorial being erected in the town to commemorate the heroism displayed by the regiment during the battle.

On a fateful day, September 29, a regimental historian would later remember, "the day dawned clear and cool. There was expectancy in the air." A fierce artillery barrage preceded the attack by the 369th, nicknamed "Hell Fighters" by the enemy. After a brutal struggle during which heavy casualties were sustained Sechault was taken and the 369th soldiers dug in to consolidate their advance position. The action depicted earned the Croix de Guerre for the entire regiment. But the Meuse-Argonne claimed nearly one-third of these black fighting men as battle casualties.

Needham Roberts was born on April 28th, 1901, in Trenton, New Jersey. At the start of US involvement in World War I in 1917, the sixteen-year-old Roberts lied about his age so he could enlist in the United States Army. After enlisting in the army, Roberts was assigned to the New York Fifteenth Infantry, which later became known as the 369th Infantry or the Harlem Hellfighters. His regiment was then sent to France where they were to be under the control of French forces. The American soldiers, who were given basic training in French language and military tactics, were outfitted with French uniforms and equipment.

Roberts and a fellow member of his regiment, Henry Johnson, had been ordered to keep watch in the Argonne Forest (France) when one day a raiding party of German soldiers (about 20 men) attacked them out of nowhere. “Though both were wounded, they continued to fight the Germans and defend the French line. Roberts’ wounds disabled him enough to allow the Germans to attempt to drag him away as a prisoner. Henry Johnson, who attacked the Germans with a bolo knife, rescued Roberts and repelled the attack, saving him from a terrible fate.”

Due to their bravery and heroics, both Roberts and Johnson were awarded the French Coix de Guerre medal. They were the first Americans to ever receive this honor. When both men returned home to the U.S., neither Roberts nor Johnson was recognized by the United States government for their feats overseas. However, a huge celebration was held in Roberts’ honor when he returned home to Trenton, New Jersey.

It wasn’t until 1996, 47 years after Roberts’ passing that the United States government awarded him with the Purple Heart. Despite Henry Johnson’s receiving of the Distinguished Service Cross and later the Medal of Honor, Roberts was never considered for either of these awards.

Roberts was disabled by his wounds, and unable to maintain steady employment. He occasionally gave paid lectures about his wartime experiences, and in the early 1940s gave radio addresses and other speeches as part of the Army's effort to recruit African-Americans for World War II. In 1949, he and his wife both committed suicide by hanging in their basement.

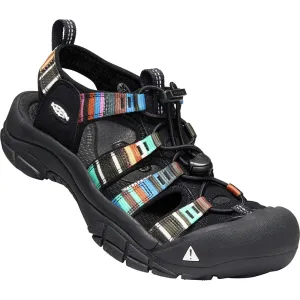

The banjo is in great shape for its age, still retaining all five strings, although they are a bit loose, and the banjo likely won’t play anymore. We have not attempted to tune or play the instrument, and being that this is an extremely important piece of history, we recommend leaving it as is. Two of the pegs appear to have been replaced at some point, but this was likely done period. It is also missing the bridge as well. It measures about 27 inches long, and is 8 1/2 inches wide. The head of the banjo is very faintly marked CALFSKIN HEAD at the top. It displays just phenomenally.

It is enough of a miracle to find an original banjo used by the American Expeditionary Forces, but to find one attributed to a famous member of the Harlem Hellfighters makes this a once-in-a-lifetime item. We have never seen one like it, and we won’t ever see one like it again. Don’t miss out on this spectacular piece of American history.

The Harlem Hellfighters

The 369th Infantry Regiment, originally formed as the 15th New York National Guard Regiment before it was reorganized as the 369th upon its federalization and commonly referred to as the Harlem Hellfighters, was an infantry regiment of the New York Army National Guard during World War I and World War II. The regiment mainly consisted of African Americans, but it also included men from Puerto Rico, Cuba, Guyana, Liberia, Portugal, Canada, the West Indies, as well as white American officers. With the 370th Infantry Regiment, it was known for being one of the first African-American regiments to serve with the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I.

The regiment was named the Black Rattlers after arriving in France by its commander Colonel William Hayward. The nickname Men of Bronze (French: Hommes de Bronze) was given to the regiment by the French after they had witnessed the gallantry of the Americans fighting in the trenches. Legend has it that they were called the Hellfighters (German: Höllenkämpfer) by the German enemy, although there is no documentation of this and the moniker may have been a creation of the American press. During World War I, the 369th spent 191 days in front line trenches, more than any other American unit. They also suffered the most losses of any American regiment, with 1,500 casualties. The regiment was also the first of the Allied forces to cross the Rhine into Germany.

Cart(

Cart(